In the frenzy of Lagos’ Berger, where the air is thick with exhaust fumes, blaring vehicles’ horns, and traders’ chatter, 17-year-old Oluwaseyi wiggles through the traffic with bottles of water and drinks to sell to commuters. Dressed in dust-covered clothes, he collects a crumpled 200 naira note from a customer and clutches it tightly.

“This is how I survive.” “If I don’t sell enough, I sleep hungry, Oluwaseyi told Allub Times’ reporter.

By the roadside, he has established a sort of home with a group of other displaced children, selling different provisions to survive, all bound by their shared struggle. Each bruise on his hands bears testimony to his resilience in the face of abuse, abandonment, and poverty.

The story of Oluwaseyi is about inconceivable suffering and surviving. Tragedy led him to the streets: the destruction of his home by flooding, the death of his parents, and an escape from an abusive guardian.

A Life Torn Apart

Oluwaseyi’s world came to a breakdown in 2022; his father died. His mother had died while giving birth to him. Before his father’s demise, the family moved to living on the farm when flooding caused by the worsening climate crisis destroyed their home in the Topo area of Badagry, Lagos.

A haven the farm once was, it became a place of unspeakable tragedy as Sewanu, Oluwaseyi’s father, lost his life on the farm after he fell from a palm tree and suffered fatal wounds. He died as he couldn’t receive proper treatment due to the family being poor, leaving Oluwaseyi orphaned.

“My father was everything to me. No one remained after he passed away,” Oluwaseyi revealed in a broken voice. The memories of his father are hazy, cloaked in the innocence of his childhood. But the pain of his loss still lingers, like an unresolved wound.

Oluwaseyi moved into his uncle’s place in Makoko, a slum area in Lagos known for its squalor and high population congestion. However, safety eluded him there. Beatings, starvation, and accusations of theft pushed him to flee.

“They treated me like a slave, beat me, starved me, and left me hungry most nights,” Oluwaseyi recounts. “They punished me without listening to my side of the story. I knew I had to escape.” One fateful night, Oluwaseyi fled and hit the streets. Destination unknown, he prayed for a better life.

He found himself on the streets, joining other displaced boys to eke out a precarious living. They sleep on streets, work menial jobs at the local markets, and beg for scraps. “I sell water, sometimes fetch it for others. It’s not enough to eat,” he says, his optimism unwavering. “I pray that one day, someone will see me and help.”

With a gentle smile, Oluwaseyi holds onto hope. “I always pray to meet a good and friendly person,” he says, his voice filled with gratitude. And in moments of kindness from strangers, he finds the strength to keep going. “Sometimes, people gift me extra money after buying from me. It gives me the strength to keep going.”

Silent Casualties of Climate Change

Oluwaseyi’s story serves as a tragic illustration of the terrible effects that violence, displacement, and climate change have on children. His tale highlights the expanding connection between human displacement and climate change.

In 2022, flooding displaced more than 2 million Nigerians from their homes. This is one of the country’s most dire occurrences. Children were immediately displaced as a result of the floods in 2022. According to UNICEF, this previous flooding cycle resulted in the displacement of over 800,000 children.

Climate change and environmental disasters are expected to further worsen, placing about 4.2 million people under threat. Children like Oluwaseyi often bear the brunt of the climate crisis.

This is also exacerbating the plight of 3.6 million internally displaced persons across the country, the majority of whom are in the northeastern part of the country, where their already fragile vulnerability has been heightened.

Conflicts also affect education. Children bear the brunt of this, accounting for 60% of the 1.9 million displaced because of conflict in the northeast. Schools in affected areas are destroyed or converted into temporary camps, leaving education as a distant dream.

In Jigawa, for instance, over 250 schools and healthcare facilities were destroyed. Furthermore, the loss of livelihoods has compelled many children to abandon their studies and work to feed themselves.

Once displaced, children face extended struggles to fulfill basic needs and ensure safety. Malnutrition, diseases from unsafe water, and the lack of healthcare are never-ending realities.

“Displacement is more than losing a home; it’s losing your sense of stability, security, and identity,” says Dr. Amadi Emeka, a pediatrician specialized in trauma in children. “The psychological scars can last a lifetime,” Dr. Amadi told Allub Times.

A Mother’s Battle for Survival

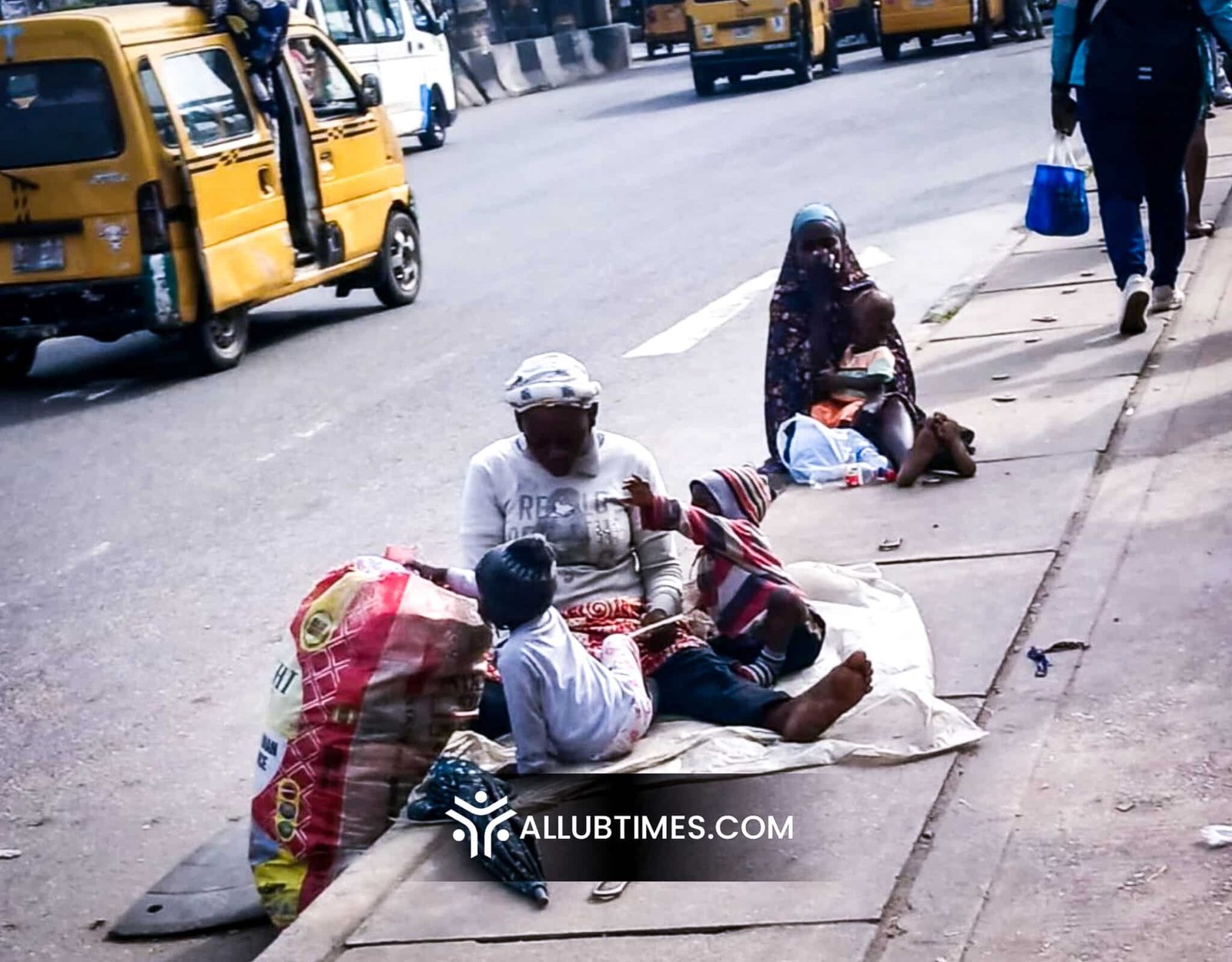

In the Ijagun area of Ogun State, Maryam, aged 49, walks the streets with two children in tow. Kareema, 4, clings to her mother’s tattered dress, while Farid, 2, sleeps fitfully in her arms. Their eyes, now sunken and weary, have seen more of hardship than hope.

Maryam, once bright-eyed and hopeful, has sunken eyes that now dimly reflect the desperation of a life consumed. Her story shows and tells just how poverty and abandonment have crushed her. Her husband fled a year ago, leaving Maryam to brave the harsh world of tending to the children all by herself. The reason for his actions? Unrelenting poverty and hardship.

“One night, I just couldn’t find my husband anymore,” Maryam says. “He left, and I haven’t heard from him since.” Maryam pauses and reflects on her next words. “The children lost their father, and he hasn’t looked back. As a mother, it’s hard not to feel abandoned, not to wonder why he couldn’t stay and fight for us.”

But what drove Maryam’s husband to abandon his family? The truth, revealed by a neighbor, is both shocking and infuriating. “I later heard he said he ran away because he couldn’t cope with providing for the family,” Maryam says, her voice heavy with anger and sadness. “But that’s not the whole truth. My husband had a problem—he gambles a lot and drinks alcohol too. He would spend all his earnings, leaving us with nothing.”

Maryam speaks words laced with sadness, anger, and disappointment. She feels betrayed by her husband’s actions, and the weight of looking after her children, uncared for and unsupported, shows in her slight frame. “As a mother, I want to provide for my children,” says Maryam. “But it is getting harder every day. We struggle to find food, shelter, and safety.”

With no income and no provider, Maryam has resorted to begging. The family’s days blend together in an endless cycle of struggle. They wander the streets and crowded markets, searching for food to eat. They beg for money to survive.

“I only want to give my children a better life,” Maryam says, her eyes brimming with tears. “I’m being compelled to swallow my pride and go on to the streets to beg. That hurts, yet I have no shame in doing all that is possible for my children. We’re just struggling to exist from day to day.”

When the sun begins to set, Maryam and the children look for a quiet corner where they can sit down. The family gathers closer together. But even amidst this despair, a glimmer of hope does still exist, a hope for a better life on another day. “I believe everything will be alright one day,” says Maryam.

A Lifetime of Trauma

To the untold numbers of children who are made to flee their homes onto the streets, it is a living nightmare that etches emotional and physical scars for a lifetime. Forced into begging, these young victims suffer unspeakable pain and trauma, the loss of innocence in the desperate struggle to survive.

The psychological burden is enormous: from witnessing violence to living with hunger to growing up in such a milieu where survival takes precedence over innocence, these children carry deep emotional scars.

The health hazard increases manifold on the streets because of malnutrition and starvation, not to mention the threat of infectious diseases. Poor hygiene and sanitation, continuous exposure to violence and exploitation, along with scarcity in health care and medical treatment, have disastrous effects.

“Children who endure displacement and street life suffer irreparable harm,” warns Dr. Amadi Emeka, a medical doctor operating in Ibadan . “The government must prioritize providing comprehensive care, including mental health services, nutrition programs, and safe shelter. We cannot afford to neglect these vulnerable young lives. The long-term consequences of inaction will be devastating.”

The effects of long-term exposure to such unpredictable living conditions result in chronic mental trauma, anxiety, depression, and stunted development. Dr. Amadi emphasizes, “Timely intervention is necessary to prevent the impact of trauma, and such children need to be given the care they deserve.”.

“It’s imperative that we provide immediate aid, including food, shelter, and medical care, as well as establish mental health services and counseling programs,” Dr. Amadi added. “We owe it to these children to act now, to give them a chance to heal, to recover, and to rebuild their shattered lives.”

A Humanitarian Crisis Ignored

Despite the glaring need for an intervention, displaced children remain largely invisible in Nigeria’s broader societal framework. However, efforts to provide basic shelter are hampered by the sheer number of displaced children and the political obstacles to implementing meaningful change. The children are abandoned by a system that should protect them.

Yet amidst this tragedy, a few glimmers of hope persist. Local organizations and humanitarian groups are taking action and initiatives to protect these children, offering them safe spaces and shelters. Some NGOs, like the Caroline Initiative, Street Child, Kaid Charity, Rising Child Foundation, and others, have introduced health and feeding programs, ensuring that at least a portion of these vulnerable children receive healthcare and food assistance.

While these efforts are a lifeline, they are limited by funding and support, leaving many families without consistent help.

Aid organizations and human rights advocates are also pushing for long-term solutions, advocating for the establishment of formal shelters, expanding feeding programs, and implementing policies that prioritize education for displaced children.

Without a coordinated response, advocates fear that the problem will only grow, creating a lost generation of children deprived of basic human rights and a pathway out of poverty.

“To break this cycle, we must protect these displaced children, offering them not just immediate relief but a future where they can thrive. Without intervention, these families will remain in the shadows,” Adebukola Temilade, a representative of Caroline Initiative, told Allub Times.

Fighting for a Future

The stories of the children are heartbreaking but far from unique. They reflect the urgent need for systemic reform and sustainable solutions to address the root causes of displacement.

Without intervention, these children face a grim future dictated by poverty and neglect. With action, however, they have a chance to rewrite their stories and escape the shadows of displacement.

For children like Oluwaseyi, survival is the immediate goal, but the dream of education still lingers. “I miss school,” he says, staring at a passing car filled with students. “I want to learn, to become somebody.”

Oluwaseyi remains hopeful. “One day,” he says, “I will go back to school. I will have a home again.” And for just this moment, a fire burns within his dusty eyes: a flash of belief.

The story of Nigeria’s displaced families, and most of all the fate of its children, is nothing less than a humanitarian crisis that demands attention and immediate action. Without a home or a school or a safe place to grow up, their futures are predetermined by poverty and survival.

For countless of the children, the journey has led them to an existence of unimaginable hardship, one where the daily question is not “What will we achieve?” but simply “Will we survive?”

This feature was produced as part of a two-part series on Nigeria’s displaced children. Read Part 1 here.